|

|

|

|

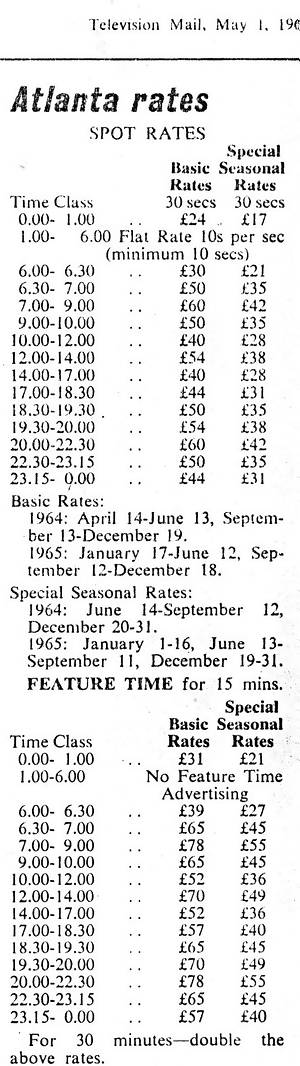

Radio Atlanta advertising rates. Cutting from ‘Television Mail’ kindly provided by Hans Knot. Click to magnify. See here for the full Radio Atlanta rate card.

|

Allan starts raising the finances and meets the man who will run a rival station - and later become his partner:

Allan Crawford: During that time, one of the people I met, who came into my office on another matter, was Ronan O'Rahilly.

Colin Nicol: When was this?

AC: Oh, it must have been early in 1963. And he leaned forward, you know - and, he's a very personable bloke, a very likeable bloke, charming manners and so on - and naturally one likes him and

like an idiot, I trusted him, especially when he said “my father's a rich man living in a beautiful house in Dublin and I'll take you to meet him. If you give me a set of the papers I'll take them to him and

interest him in investing - being one of your investors. So I went over to Ireland. He was absolutely right - beautiful house on the outskirts of Dublin. The father himself drove us to the border, to this port, Greenore.

There were weeds. It hadn't been used for a long time, this part of the port. It had been a popular railway thing for trippers years before and it had fallen into neglect. But there was a jetty for ships to tie up

alongside and so on and he said you can come here. It'll be kept quiet. You can equip your ship and I'll see to it that you don't have any trouble, etc.

CN: Did he own that port or did he just have influence?

AC: Well, according to Ronan, he practically owned it and I accepted that what he said could be done, would be done - and, in fact, it was done except that, by that time, Ronan himself had used my

papers to run out and get his own set of backers and buy his own ship and eventually it ended up being tied to this jetty and our ship came and had to tie up alongside it - and, of course, as rivals - but with the same

maritime advisor.

CN: Ronan probably worked on the project for a full year before Caroline went on the air. Would you say that?

AC: He didn't get the papers from me until a month or so after I met him - that would have been early in '63 I suppose - and he didn't have to work on it. He only had to work on getting the money.

I'd done all the work. He didn't do any work. He used exactly the same people I'd already chosen. In every respect except the lawyers, and they didn't need to do anything because they'd got my lawyer's papers.

CN: How did he get hold of the papers?

AC: Well, because I gave them to him for his father as a potential investor.

CN: How did you choose the ship's anchorage?

AC: In my researches I had tracked down a set of pilots operating the ships in and out of London. They were great blokes and of course, they knew the waters like the palm of their hands.

CN: This was the Trinity House involvement, wasn't it? They became investors in Project Atlanta.

AC: That's right. It wasn't an official thing. It was only with some of the people who were involved and they brought in shareholders that they knew, people with money and so on. There was a little

clique of investment from that direction that was always friendly with me in particular. They looked at the maps very closely and they found a perfect spot for our ship.

CN: And that was chosen because of a sheltered location between sandbanks?

AC: Oh yes. It was the best sheltered location for probably two hundred miles - three hundred miles and that was one of the things I always withheld from Ronan. He never knew where this was to be.

All he knew was that it was off Frinton but he didn't know where. And he didn't know anyone closely enough as I had done ..

CN: In Trinity House?

AC: He hadn't thought of doing that you see, because unless I told him something, he never got a new idea. So I withheld this information - it was always my secret - so when his ship arrived sooner

than mine - because when the two ships were tied up and in opposition and getting ready, the sabotage that was going on in my ship to stop it getting ready was colossal. In fact, the influence that Ronan brought to bear

was such that our ship was ordered out of harbour several times by the people that were the harbour masters or whatever. In fact the Captain was forced to go out during a storm once and it was so bad that the ship touched

bottom in the harbour. He turned around and came straight back in and said “up you, I'm going to stay here” and knowing what they were doing, they didn't dare do too much about it. But it meant that Ronan's

ship got ready earlier. Even the ship's rigger that I discovered, a lovely man from Devon with a marvellous accent you could cut with a knife. He was the rigger that rigged our ship but Ronan got on to him through me

too, and he was used on theirs. So he was rigging both ships, and so on.

|

|

|

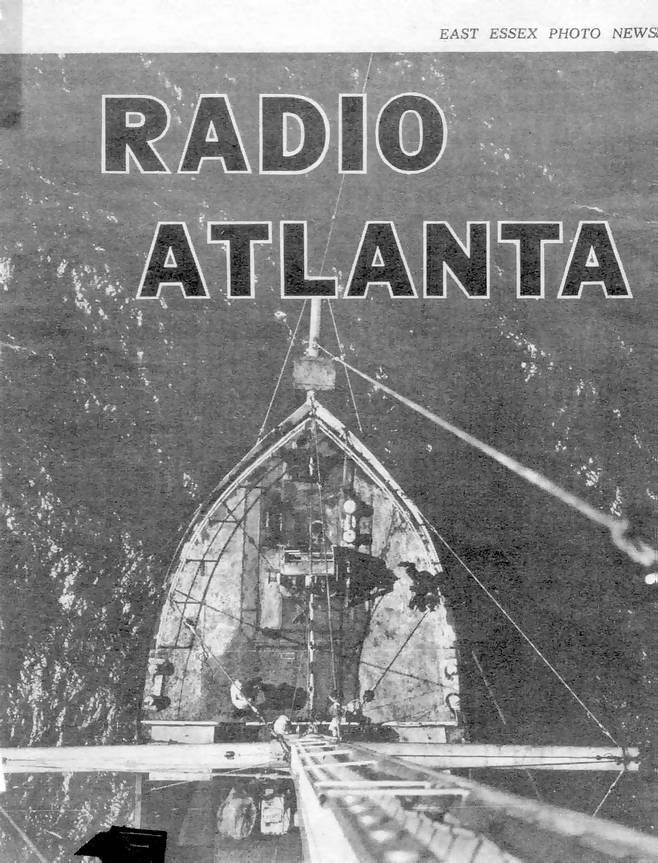

Radio Atlanta's ship, the mv Mi Amigo, from above. Cutting from ‘East Essex Photo News’ kindly provided by Johnny Jackson. Click to magnify. For more of Johnny's

memorabilia, see here.

|

CN: What other incidents occurred in Greenore?

AC: Oh, hundreds of incidents. I had people reporting to me by phone every day about - you know, there'd be things mysteriously - wires cut, all kinds of things. You couldn't get on our ship without

climbing over the other one first. What was that called? Yes, the Fredericia, and it was much bigger. I had a hell of a lot of headaches there. In fact, in order to get out of harbour eventually, when it was ready, we

virtually cut cables and sneaked out because there was no other way of getting a clearance from these bastards. It was going to be impossible, so we simply left. Then I got a telephone call at about four o'clock in the

morning. The ship had been in heavy seas off Falmouth and it had to go into Falmouth because the mast was coming adrift, because it's a high mast - it was 153 feet I think. Anyway, much too high for a ship of about 170

feet long, so I had to send £100 in cash and all kinds of things to get my rigger to get in his car to get straight to Falmouth and repair this, which he did. Then they left harbour again and came on its position.

CN: At this stage, the ship hadn't transmitted after all ..

AC: No, no, no, no.

CN: She wasn't recognised as a radio ship.

AC: No. That's true. I mean there were rumours about Mi Amigo - it was all over the place. You can't trust reporters to be honourable about news.

CN: But, of course, by this time, Caroline had gone out on the air anyway, so ..

AC: That's right. And so we came on a couple of weeks later into the correct station between two banks which protected it to a great degree - although you can't tell some of the DJs, with the weather

that they had....

CN: But it was a protected place ..

AC: Then our first test broadcast was done by trickery because we broadcast in French, so that people couldn't tell that we were testing for ourselves. My secretary, Margaret, did this and we sent

the tape out. Successfully broadcast. So we had our test done and this lovely engineer that we had....

CN: Thomas..

AC: Thomas. Mr. Thomas, yes of course. Very fond memories of him. Absolutely ethical man and knowledgeable.

CN: Can I ask how you found your finance in the first place, who your shareholders were, and how many of them there were? There were a lot, weren't there?

AC: Yes, there were a lot. Some for quite small sums and we had painfully to go round seeing many, many people in order to get the money together. In retrospect, twice the amount would have been

handier and we could have weathered the storms more easily but we couldn't have asked for that amount. It was difficult. It takes a certain type of person to take a gamble. I was always saying to them, “When you

put this money in, write it off - at once - and then if something good comes out of it, OK.” So, as far as I know, we never got widows putting in their life savings!

CN: Where there as many as 129 shareholders?

AC: Oh yes. I would have thought so. Over a hundred anyway. And, as I said, the biggest single lot couldn't have been more than ten or twenty thousand pounds.

CN: And how much was raised totally?

AC: Well, I think that we went for about a hundred and fifteen thousand to start with. I think that we went for another share issue later, which wasn't very much. That probably took it to, I think,

a hundred and fifty thousand. And then we had a loan from (sports promoter) Jarvis Astaire's direction. And that's about the extent of it. In hindsight I would say we would have managed far better on about a quarter of

a million, but I'm pretty sure that, if we'd asked for that, we wouldn't have got it.

CN: How much do you think Ronan and his group had?

AC: I don't know their circumstances.

Radio Atlanta launches - but soon runs into trouble:

|

|

|

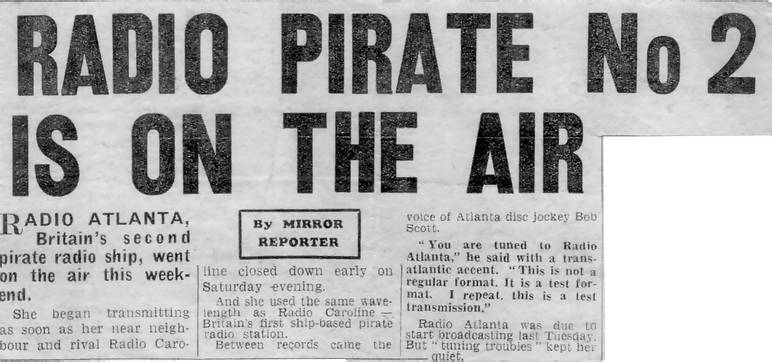

Radio Atlanta is on the air. Cutting from the ‘Daily Mirror’ kindly provided by Johnny Jackson. Click to magnify. For more of Johnny's memorabilia, see here.

|

AC: We had everything running on the ship, we had the test broadcast, then we started. The opposition from Radio Caroline itself didn't bother us. We had to teach the advertising

business in England how to assess the worth of a broadcast so that they could know what to tell clients they could pay. Which got us involved much more heavily than I anticipated in doing surveys. All the time, surveys.

Of course, that's the secret of it. I had, during my research period, naturally gone to meet the people with the Dutch ship, Radio Veronica, the Verweij brothers, and I took a great liking to them. In fact they needed

money very heavily in 1961 or 62 and would have loved to have had partners with that extra money. Because they'd struck the same kind of opposition from the authorities. People were afraid to advertise and I found an

English bank, the partners of an English bank, a small bank, willing to listen. So, I took them over there on a beautiful summer's day - must have been '62 I suppose - might have been '61, and they went out to the ship,

came back and we started to talk to the Verweij brothers. Only one of whom ever made the decisions. The other three were underlings. But one of them loved radio - he wasn't the decision maker - and the English people

started to talk and the day was such a nice day they were so bloody light-hearted they started to get flippant. And the Dutchmen didn't like it. I mean they were in trouble, they wanted money and they weren't interested

in anyone getting flippant on a nice summer's day, and they grew to dislike the group of people I'd taken, which was a shame because they only needed a few thousand pounds. Anyway an agreement was almost made - but then

we reached the point where someone had to pay a couple of thousand pounds for a survey. The British said “why should we pay for it?” and the Dutch said “well if you want to be partners, you damn well

have to pay for it.”

CN: This was to be a survey in Holland on...

AC: Their operation. Radio Veronica. And we came back to England, with them not having reached a decision, and it's always bad not to clinch a thing on the spot. The deal failed but within days one

of the biggest companies - I might be wrong in saying it was ICI, but it was a company of that calibre, maybe Kelloggs - had some kind of adverse publicity and they needed a quick way of counteracting it. They chose to

advertise on Veronica and, overnight, they were making two thousand a week instead of a loss - and they didn't need us any more!

CN: Two thousand then, of course, is twenty thousand now.

AC: Yes, yes that's right. And, so they didn't need us. Of course, I kept in touch with them.

CN: This was fairly early ..

AC: That's right, about 61.

|

|

|

Colin Nicol “frigging in the rigging” on board the tender Offshore I. Photo by David Kindred, provided by Colin.

|

CN: This was a fairly early brush with pirate radio for you, shortly after you decided you were going to follow up the idea.

AC: Yes, that's right. I'm putting things out of order I know, but my memory is leaping all over the place. But getting back to Atlanta. We were on station and on air but we found that we needed to

go much more heavily into surveys than I'd estimated originally. Nobody knew that we needed to do this. In fact, if it had been obvious, we'd have done it. Anyway it put greater strain on our money resources and, all

the time the current whoever he was - Postmaster General - would stand up and say “this is illegal!” Our advertisers - that we were painfully getting together with a struggle - would stop advertising because

they'd believe him.

CN: So then there would be a scare.

AC: Then there would be a scare, the income would go down and we were in trouble. Then weeks go by and we weren't off the air and people would get confident and come back again. Then there'd be

another announcement in Parliament: “We are passing an Act to stop this” and so on, and people would believe it again. So our income was erratic. It didn't build up gradually as it should have done. And,

of course, the same thing was happening up the road, a mile away, to Radio Caroline. Both ships were crewed and supplied by the same Dutch Wijsmuller company, so our Dutch Captain, Captain de Jong, got us together with

the lawyer that we had (he was my lawyer in Liechtenstein - and, of course, naturally, Ronan used him too!) and we met in the beautiful offices of this man in Liechtenstein, with the Captain being the Chairman. He was

anxious that this thing would work and he more or less twisted our arms to get together using Radio Caroline as a name. I was very reluctant because I thought that Radio Atlanta was a much better name. But Ronan was

always manipulating, manipulating - never stopped. He would have been marvellous in Tammany Hall, you know, in its hey days in American politics, arguing you know, supplying the gift of the gab and the arguments.

CN: Why did he choose Caroline for a name?

AC: Well, it's because he came across the Tory Chancellor at the time ..

CN: Maudling?

AC: Maudling, Reginald Maudling, who had a daughter called Caroline, and Ronan met her at a party and thought that we would be able to, stupidly, thought that we would be able to influence Mr. Maudling

in our favour by naming it after his daughter! Obviously as a politician, he couldn't do a thing and he never did, quite rightly. So we gained nothing from this bloody silly name, Radio Caroline.

CN: He later said that it was named after Caroline, President Kennedy's daughter.

AC: No, no, no, no, no.

CN: But that's the accepted version ..

AC: Yes. I don't even know if Reginald Maudling had a daughter called Caroline because I've never asked but that was the story I got.

(Webmaster's note: In a conversation with Colin Nicol and Keith Martin on 30th January 1984 Michael Parkin, Managing Director of Caroline Sales, said that “Ronan named Caroline after

Caroline Maudling as he was a bit keen on her at the time.” And in another of Colin's interviews, Radio Atlanta's General Manager Richard Harris agreed. He said: “The name Caroline

came about, as the story has been told to me, because he was dating Reg Maudling's daughter whose name was Caroline and he named the station after her. He said later of course that it was named after President Kennedy's

daughter Caroline.” Of course Allan, Michael and Richard may all have heard the story from the same original source and, just because three people have repeated it, it doesn't necessarily mean it is correct - but

it is certainly an interesting theory!)

CN: You were talking about the deal with Caroline.

AC: Someone had to be cooperative and I swallowed my pride, having been the creator and I was losing my own created name.

CN: When it came to the merger, what sort of date was it when that occurred?

AC: It would have been about three or four months after we started and we started about the first quarter of 1964, so we would have been forced into each others arms around July I guess. Something of

that order. In July of '64.

CN: And shortly after that, Caroline, the Fredericia sailed north.

AC: Well, it would have been a matter of days after this agreement being made in Liechtenstein.

|

|

|

A tender approaches the Mi Amigo in rough seas. Photo taken by Carl Thomson and supplied by Colin Nicol.

|

CN: Did you both go over there?

AC: I went over with my Chairman, and certainly Ronan met us there and Captain De Jong, and I don't know who else was with Ronan. I forget. It might have been (investor) Jocelyn Stevens or somebody

else. So we became Radio Caroline, North and South, with the agreement that his ship would go round to the Irish Sea off the Isle of Man and we would operate as a network and share the income. It was agreed that it would

be fifty-five percent to his lot because they said they'd put in more money for the bigger ship and forty-five to us and, at a certain stage of income it would merge at fifty-fifty. I made another mistake there, which

was not to set a time limit on that. In other words, if the income didn't reach a certain point within a certain time, it would go fifty-fifty anyway. So, we were always at a handicap from an income point of view as

compared to Ronan's side. Well, you make these mistakes. However, that wasn't the mistake that killed us. It was the fact that we'd underestimated on capital in the first place. I went over to the Verweij brothers to see

if they would ... I realised that, if we could stop operating in a rocking ship at sea, we would be better off if we had a stable platform still outside the three-mile limit. So I looked around and, with the help of my

Trinity House pilot friends, nothing official with Trinity House of course - we pinpointed a number of gun platforms that had been built at enormous expense during the war by the British and abandoned.

CN: Out in the Thames estuary.

AC: Out in the estuary. These very large structures were still there. So we went around in a big launch and we made a list of the ones that we felt were outside the three mile limit. We got a legal

opinion with big maps and so on that this was so, and on this basis I then went to get extra money from my friends the Verweij brothers in Holland. I went back to see if they'd invest in us.

CN: Yes. They hadn't invested up to then?

AC: No. They hadn't been asked. But they were very prosperous at that time.

CN: They were stocking manufacturers, weren't they?

AC: Yes. They had a successful hosiery business and I saw the factory and what-not when I went to see them. They used to come and fetch me in cars whenever I came to the airport and so on. I believe

they had some legal trouble later on through some arson charge. I can't believe it. They weren't that kind of people. Anyway, I went to them and, in principle, they would be interested if we put a transmitter on one of

the rigs that we'd picked, but it fell through because the Postmaster General of the time stood up once again saying “it's definite that this is an illegal operation”.

CN: The forts or the ships?

AC: The ships. They didn't know we were going to do anything about the forts at the time.

CN: I remember talking to you about forts in early '64.

AC: Yes. It would have been about that time I was involved in that.

|